The bomb that destroyed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City killed 168 people - including 19 children. It injured hundreds more, and forever shaped the community.

April 19, 1995 started as an idyllic spring morning - clear skies, calm winds - better than most Wednesdays during the state’s usually-turbulent severe weather season. Nothing seemed out of the ordinary. Workers showed up to their jobs, and went about their regular routines.

That all changed at 9:02 a.m.

KGOU, KOSU, and our partners with the Oklahoma Public Media Exchange have spent hundreds of collective hours talking to Oklahomans to tell the story of that day in April.

Jason Williamson was a 24-year-old phone teller at the Federal Employees Credit Union, located on the third floor of the Murrah building on April 19, 1995. Williamson had woken up early and gone to work. He was on the phone with a customer when the bomb detonated.

His desk was 10 to 12 feet from the teller line that fell into the large crater.

Williamson noticed a split second of darkness before the explosion.

“It was an incredible, deafening noise,” Williamson said. “I had the sensation as though I was falling very quickly and very violently.”

Williamson wasn’t falling, and he now attributes that feeling to all the other floors collapsing around him.

“Everything was just a complete void. Just a blackness that I had never experienced before. There was no sound. There was no smells that I remember. Just this utter dark void,” Williamson said.

“I was assuming that I was dead at that point. I just remember feeling sort of a sense of relief that it had been quick and painless.”

Williamson realized he was alive when he could move his fingers little by little. Eventually, the blackness gave way to gray which later gave way to light.

The light was coming from the outside of the building, now that the north side of the Murrah building had been reduced to rubble.

“What finally broke me out of this state I was in was hearing a coworker of mine, Bobbi Purvine, screaming, ‘What happened? What happened?’ That woke me up. That snapped me back into reality,” Williamson said.

Williamson helped her climb over her desk and was joined by another co-worker. The three of them stood in shock, looking outside. They later found another co-worker underneath a desk.

News helicopters circled overhead while burning cars sat in the parking lot across the street. Williamson heard popping sounds everywhere, which he thinks might have been the sound of broken glass.

“The combination of all of these factors made us think, maybe the city was under attack,” Williamson said.

Williamson and his coworkers maneuvered around the debris to find a hallway that led to a stairway on the south side of the building where they were able to escape.

He survived with only minor wounds which eventually healed. He didn’t lose any family members in the bombing and that has allowed him to come to terms with the tragedy.

“I don’t think it’s ended yet for so many people who lost family members and that’s something they’re still dealing with,” Williamson said.

He later went to Timothy McVeigh’s trial in Denver for a week, where he experienced a whole range of emotions as he would stare at the bomber.

“It was an extremely strange feeling to be sitting just a few feet away from this man who caused so much pain and devastation and who also tried to murder me - who did murder 168 other people,” Williamson said.

He received an invitation from the Department of Justice to view McVeigh’s execution in Terre Haute, Indiana or via a closed-circuit television screen.

“Viewing it was something I just could not imagine taking part in,” Williamson said.

Bill Kenney was in an advanced cardiac life support class in a building about two blocks west and five blocks north of the Murrah building. About a third of the classroom’s drop ceiling collapsed, and the bomb blast sounded so intense that Kenney thought it came from the building’s garage.

“We thought it might have been a fire in the garage. Maybe one of our vans had exploded,” Kenney said.

At the time, Kenney was the training coordinator for the Emergency Medical Services Authority, or EMSA. Once they figured out the blast did not come from their own building, he and other paramedics rushed to the back door. It was jammed shut so they had to kick it down.

“As soon as we were outside and could see around the building, we could see the smoke starting to rise from downtown,” Kenney said. “We knew that the blast had been close.”

He jumped into a vehicle with other paramedics and arrived at the Murrah building about two minutes after the bombing.

“The original thought was that there may be three or four hundred people in the building, and that meant that we had to expect possibly three or four hundred injuries,” Kenney said.

The scene was chaotic as people started to leave the surrounding buildings, milling about and running in all different directions because nobody was sure what was going on.

By 10:05 a.m., Kenney’s team had transported 110 patients from the blast site.

“Lots of cuts. There were bruises. Very few burns. In fact, there was no real fire at the explosion site. There was a fire in the parking lot across the street,” Kenney said. “We had some crushing injuries and unfortunately we had a couple of falls - people just trying to get away or get out.”

Kenney estimates that 70 percent of the people he treated were from surrounding people or the street.

After a patient is triaged, Kenney said medics need to make a quick decision about the severity of the patient’s wounds. Some minor injuries didn’t need treatment or could wait while more serious injuries are addressed. Major injuries are treated immediately, but some injuries are so severe that they are considered a “black tag” - no amount of treatment will help that person survive.

“In a disaster situation, that’s a very real category,” Kenney said.

One rescue worker brought an infant to Kenney whose injuries were so severe that he described them as “incompatible with life.” He handed the child to a female medic and told her to put the baby in the ambulance that was serving as a morgue for children. The female medic noticed the baby was still breathing and that she could not lay the child down to let it die alone, so she sat in the ambulance with the baby and rocked it until the breathing stopped.

“I’m very, very moved by that instinct of her not being able to lay that baby down to die by itself,” Kenney said. “I think that’s the kind of bravery we saw in all of our medics, and for that matter, all the first responders that morning.”

Medics remained on the scene every day until the Murrah building was demolished. Kenney said the community came together during this time and “had each others’ backs,” he said. Strangers would approach him and bring him bottles of water and ask if there was anything else he needed. People wanted to help in any way that they could.

“I think at the time, it brought the city together,” Kenney said. “We were all Oklahomans. Okies.”

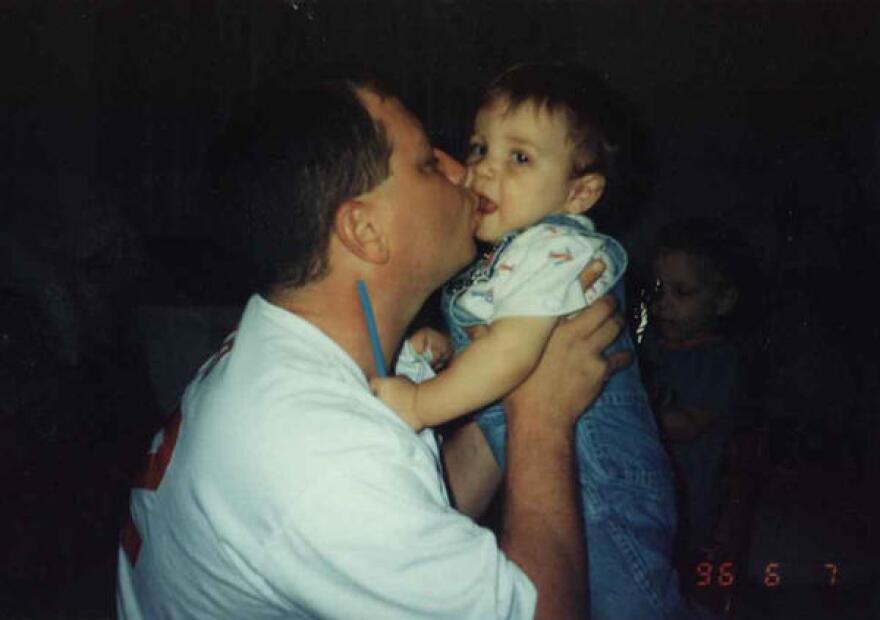

Kevin McCullough was an Oklahoma City police officer and an EMT for EMSA in 1995. He was the father of three kids, and his wife was pregnant with their fourth child.

McCullough had the day off work, and he was taking an ambulance to a group of homeschoolers in Moore to teach them about the importance of first responders.

“I just heard on the radio they had initially advised us that the fire department felt like it was a natural gas explosion, and they requested all available personnel to report to the bomb site,” McCullough said.

He turned the ambulance around, picked up a colleague at the EMSA headquarters and arrived on the scene.

“The first thing that I really noticed was the nitrates in the air from the bomb. It smelt a lot like we were out at the firing range shooting our weapons. To me, it was a very similar odor. But it was much stronger,” he said.

Throughout the day, McCullough worked on removing bodies from the Murrah building. Phone lines were down, so he didn’t realize his family was trying to get in touch with him until he returned home late that night.

“I describe April 19, 1995 as one of the worst things that ever happened to me in my life, but also one of the best things because as I was down here working in the rescue efforts in the bombing. Unbeknownst to me, my wife was in the hospital giving birth to my youngest son Jordan,” he said.

It was the only birth of any of his children he missed. And as hard as it was for McCullough to not be in the hospital during the birth, he says the timing his son’s birthday turned out to be perfect.

“Looking back, that I needed that. At the end of a day like that, when you just don't know what to do, you just don't know what to think, you're at your wits end, and you’re both physically and mentally exhausting, that's where I was at that time and I needed that. That's what I needed.”

McCullough tends to stay away from the Oklahoma City National Memorial. He only visits when he’s asked to speak at the museum or attend an event. No matter how many years pass, McCullough says it still can be emotionally taxing.

“It's very difficult for many of us that responded,” he said. “It's difficult to talk about, It's difficult to visit this place, but when we do, it's with respect. It's wanting to maintain the dignity and realizing that we won't forget,” McCullough said.

For nearly four decades, Lisa Sielert has dedicated her life to early childhood education. In 1995, she taught kindergarten and also served as an adjunct professor at the University of Central Oklahoma.

One of her students, Dana Cooper, had just gotten a job as the director of the America’s Kids daycare on the second floor of the Murrah Building.

It was a brand new facility, and she could take her two-year-old son Anthony to work with her.

But on a Wednesday morning, Sielert took roll, and Cooper wasn’t there.

“We started talking. Where did she work? She was downtown. And then little by little our memories came back that, yeah, she was in the federal building,” Sielert said. “Before the evening was over, we just knew in our hearts that she had been there. We didn’t find out until the very next day that indeed she was on the list, not only Dana but also her young son Anthony was lost in the bombing as well.”

Susan Urbach had just sat down at her desk at the Journal Record building across the street from the Murrah building, waiting for a 9:00 a.m. appointment on April 19, 1995.

All of a sudden, everything caved in as the building shook so hard she couldn’t stand. She managed to pull herself up from the rubble, but the blast had the buttons from her top and knocked her shoes off her feet. She and her colleagues walked in their stocking feet through hallways covered with shards of glass, eventually managing to make it to the street and to triage by 9:30.

“One of the things that was traumatic for me was seeing a friend down the hall, Pauly Nichols, who was put next to me on the street, who was just dead weight,” Urbach said. “She only had one cut, but it was the one in her neck.”

She spent hours in surgery to repair her lacerations, and estimates she received four feet of stitches if you laid them out end-to-end. After coming home from the hospital, staying with friends, and spending time with her parents, she went to St Gregory’s Abbey in Shawnee.

“I slept for three days. That’s all I did. I went to be with the monks and the prayers and just kind of being in a sanctuary,” Urbach said. “I think that was probably one of the absolute best things to have done. You need to remove yourself and get yourself very centered. And for me to be very centered is centered around my faith.”

Urbach used to work in the Murrah building, and knew seven people who died. Downtown Oklahoma City is her community. Her church, St. Paul’s Episcopal Cathedral was heavily damaged, and she was a member of the downtown YMCA just northeast of ground zero. She says the bombing was a community event, not just because of the physical destruction, but because of the constant reminders like the trials of Timothy McVeigh, Terry Nichols, and Michael Fortier, and the redevelopment of downtown.

“For the people that I knew at least and who are still working downtown, for example, I always know that’s a connection. It’s like being a war buddy,” Urbach said. “You know, no matter what happens, there is something that’s a very deep connector to you. It’s absolutely amazing because downtown is so different from 20 years ago.”

For Urbach, healing comes gently. The bombing threw open the unanswered questions of life - why me? Why not me? Why does someone do this? What is a senseless act?

“There are so many major kinds of issues that for me, one of the things that it did was to cause me to sit down and really ponder many many many many different kinds of things,” Urbach said. “And I think the greatest takeaway of the bombing is, you know what, life is really short. Life is temporary. You know the things that matter are love.”

Architects Hans and Torrey Butzer designed the Outdoor Symbolic Portion of the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum while living in Germany in the 1990s. They were challenged to create a peaceful place that still commemorates a violent act.

“We also wanted to recognize the people who survived, we also wanted to recognize the people who helped, because that is such an invaluable part of the story,” Torrey Butzer said. “There was this bad thing that took place here, but what happened afterwards was so exponentially wonderful.”

The memorial sits on the site of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, NW 5th street, the location of two buildings damaged beyond repair, and and the former parking lot across the street. It’s a reverent, personal and sacred site - deeply moving to all who visit. Hans Butzer said his wife read about each of the victims to understand their stories.

“And from there [she] gained an insight into the deep sense of emotional loss, as well as recognizing, ‘Wow, this is a civic memorial that’s going to become a national memorial. It’s still about the loss of 168 individuals,” Hans Butzer said.

A metal and glass chair honors each victim in the footprint of the building, arranged by the floor they were on at the time of the blast. A small light illuminates the base at twilight, casting a glow across the reflecting pool that follows the path of NW 5th Street the north end of the building faced.

“The other day I was reading our daughter, our youngest daughter, a story. It was a picture book. It was about a little girl who just loved her grandfather and they did all kinds of things together. And then she went into the room one day, and it said the chair was empty,” Torrey Butzer said. “And that implied to the readers of that story that the grandfather had died, and she was very sad. So this image of the empty chair … there’s very few words needed to kind of explain the bigger context of what just happened.”

From the beginning, the Butzers felt strongly that they wanted the memorial to become integrated into the fabric of the city. It serves as a public and civic space, but also a green space, a park. Enough formality to be reverent, but accessible enough for residents and visitors to move through easily.

“It’s like a quiet plea to visitors - to learn from this, and see how you can rededicate every day to one little thing to make this a better world,” Hans Butzer said. “And the easiest way to do this is to instill a greater sense of goodness in others and to lead by example.”

"That April Morning: The Oklahoma City Bombing" is a production of KGOU, KOSU, and our partners with the Oklahoma Public Media Exchange.